Longford writer Maria Edgeworth was famous in her day (1768 – 1849) for writing stories for children, novels for grown-ups and essays about education for parents and teachers. You can find many of her books in the Pollard collection at Trinity College Dublin. Edgeworth believed that books like Gulliver’s Travels and Robinson Crusoe shouldn’t be given to adventurous boys, unless they were going to enlist in the army or the navy and have a very exciting life anyway. Edgeworth thought that if boys got a taste for adventure, they would never have the patience to study or get a sensible job.

Not a real newspaper – see below!

She said books about travel and adventure were not as dangerous for girls, who already knew that they were never going to ramble around the world in search of adventure. Boys, however, thought fame and fortune were easy to find, Edgeworth said, and though the adventurous life is like a lottery, boys always thought they were going to win.

Maria Edgeworth by John Downman (1807)

The funny thing is that Edgeworth herself enjoyed the excitement of travelling. She had been born in England and moved to Ireland after her mother died when Maria was five. Her father, Richard Lovell Edgeworth, had an estate in Longford in a town that became known as Edgeworthstown after the family – its older name, Mostrim, is also used today. A few years after Maria and her father wrote the book Practical Education, which gave all this advice about the dangers of stories of travel and adventure, Maria went to London with Richard and his fourth wife, Frances. Between 1800 and 1803, the family toured England and then went to Belgium and France.

Although Edgeworth’s ideas about the differences between girls and boys when it comes to adventure seem old-fashioned today, in her day some of her views were considered ‘modern’. At a time when most schools were just for boys, and women were not allowed to vote, she believed girls and boys were equal and women should be just as well educated and as politically active as men.

By the way, that’s not a real newspaper from 1798 above – it’s one I made up because I thought it looked exciting.

ACTIVITY: Write a letter to the newspaper above, agreeing or disagreeing with Maria Edgeworth’s views. Maybe you are a girl or boy sailor or traveller, maybe you think everyone should read these books, or maybe the books influenced you in a good or a bad way. You can be yourself or a person from Edgeworth’s own time. If you send your letter as a comment by posting it in Leave a Reply (below), you might see it published on its own newspaper page like the one above.

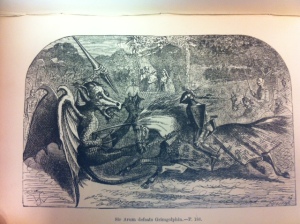

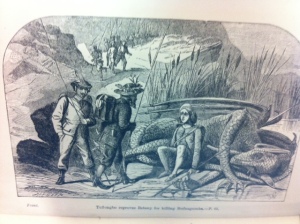

Illustration from Rosamond: A Series of Tales by Maria Edgeworth, digitised at Roehampton University

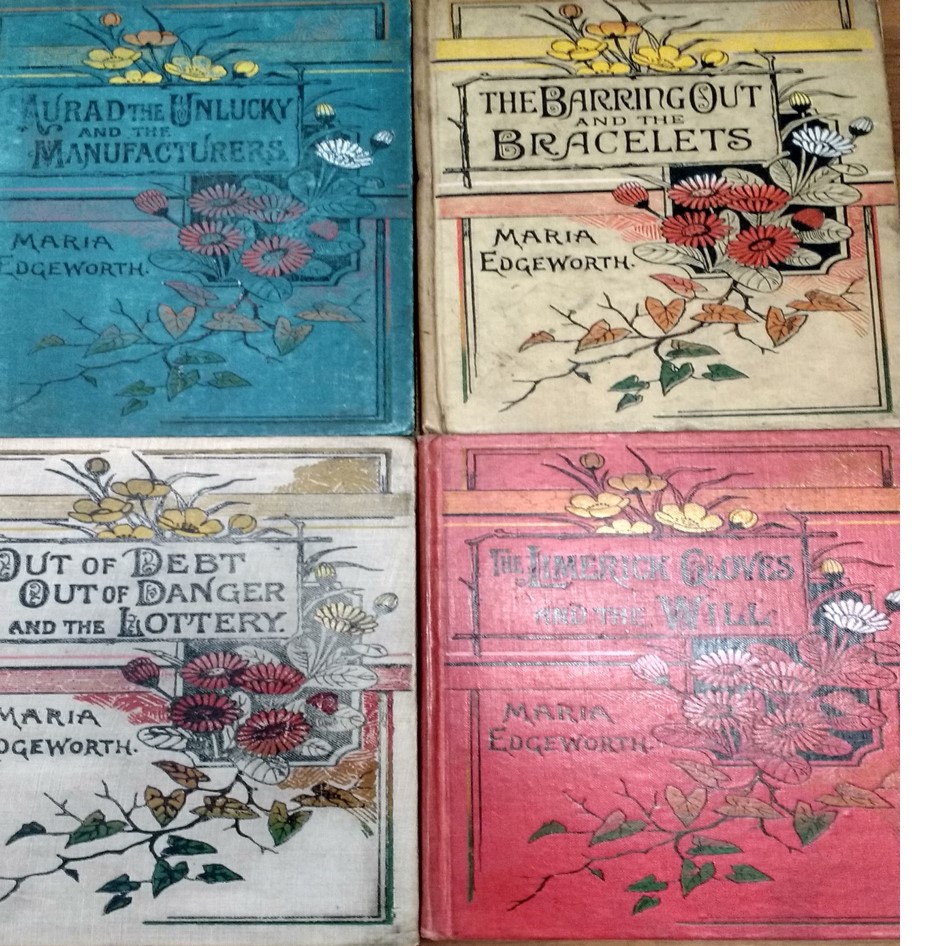

MORE ABOUT MARIA EDGEWORTH – Many of the books by Edgeworth in the Pollard Collection are from the 1880s and 1890s, even though some of the stories were first published in 1796. This shows that Edgeworth’s work was popular for over 100 years.

In 2012, some of the books by Edgeworth in the Pollard collection were brought together by Principal Librarian in Early Printed Books and Special Collections, Dr Lydia Ferguson, for a presentation to students of children’s literature there. You can see some of the beautiful covers below.

Clockwise from top left: Murad the Unlucky and The Manufacturers (London, [ca 1890]); The Barring Out and The Bracelets (London, [ca 1890]); The Limerick Gloves and The will (London, [1889?]); Out of Debt, Out of Danger and The Lottery (London, [ca 1890]) all published by George Routledge of London. .

You can read Maria Edgeworth’s story for children, The Purple Jar, by clicking here, and another story, The Happy Party, here. Both stories are from the collection, Rosamond: A Series of Tales, which has been digitised at the Children’s Literature Digital Collection at Roehampton University.

by Barbara Hawes, 1844 edition

by Barbara Hawes, 1844 edition  by Baron La Motte-Fouque, 1862? (translated from German)

by Baron La Motte-Fouque, 1862? (translated from German)